Trio of British track cyclists target three new world records

A trio of British Olympians and para-cyclists will be attempting to break three track cycling world records this month.

Double Olympic silver medallist Matt Richardson is aiming to break the record for the fastest flying 200m lap and to break the nine-second barrier for the first time, while Paris team pursuit silver medallist Charlie Tanfield is attempting to set a new men’s elite Hour Record, which is currently 56.792km.

Para-cyclist Will Bjergfelt is targeting the men’s C5 Hour Record, which has stood for more than a decade, and is hoping to become the first para-cyclist to ride more than 50km in the process. The current record of 47.569km was set by Andrea Tarlo in 2014.

Richardson, who formerly raced for Australia before switching to represent GB last summer, briefly held the 200m record during the Paris Games before his rival Harrie Lavreysen broke it, setting the benchmark of 9.088 seconds.

Speaking to media including The Independent before the event, Richardson says his motivation “is to become the fastest track cyclist of all time.” He and Lavreysen – who picked up three golds in Paris – have developed one of the sport’s closest rivalries and the chance to go clear of the Dutchman is a major drive behind the record bid.

He says: “For me, it’s a bit of a race between Harrie and I to be the first person to do it. It’s been on my radar for the last couple of years. It’s going to happen at some point, and once someone goes sub-nine [seconds], they’ll be the first person to do that, forever. Records get beaten all the time but barriers stay with that person.”

Bjergfelt was a successful road and mountain bike rider before he was hit head-on by a car in 2015 and suffered life-threatening injuries, with his right leg shattered into 25 pieces. He returned to racing in the C5 para-cycling category, winning a world silver medal on the track in 2019 and a world road race title in Glasgow two years ago, and was the first para-cyclist to ride the Tour of Britain.

The Bristol native says, “The Hour Record is iconic. I jumped on it straight away because it’s something I’ve wanted to do for a long time.

“I definitely want to see if I can crack 50km. I would be the first C5 para cyclist to break that barrier, so that would be pretty special. I feel like I’ve done some pretty incredible things since I became a para-cyclist, so I want to put it out there that if you have an impairment or a disability, there’s so many amazing things you can do, and it shouldn’t hold anyone back who has aspirations. I want to try and inspire people to get involved.”

All three world record attempts will be taking place on 14 August at the Konya Velodrome in Turkey, which hosted a round of the UCI Track Cycling Nations Cup in March. Richardson momentarily thought he had eclipsed Lavreysen’s record at the Nations Cup, clocking a time of 9.041 seconds in qualifying, but the UCI voided his time as he strayed beyond the official bounds of the track.

But the seeds were sown for future attempts. Bjerfelt says, “With British Cycling this year being inspired by Matt’s ride at the World Cup, everyone got really excited about the velodrome in Konya. That pre-empted the whole [idea], let’s go back there and smash a record, and open it up to everyone.”

Richardson explains, “What makes this so appealing for a flying 200m is it’s a very similar shape to the Paris velodrome [in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines], which is deemed probably one of the fastest sea-level tracks because of how wide and steep it is, but they’ve basically plonked it at 1200m of altitude. For a flying effort it’s pretty optimal.” That steep banking allows riders to pick up more speed as they fly down to the bottom of the track, while the lower air pressure at altitude contributes towards lower air density, which means the riders will face less resistance. As Bjergfelt says, “with the same power, you travel a lot faster”.

Of his brief spell as official world record holder during the Paris Games, Richardson says, “It was a bit of mixed emotions, because I didn’t realise I’d broken it when I had, because you’re so locked in to the competition.

“My first thought was ‘that was a quick time’, and then it dawned on me when I heard them announce that whoever wants to be the fastest qualifier now is going to have to break the world record. I was like, ‘I got it, didn’t I?!’ And then 30 seconds later I watched Harrie go round the track, and was like ‘and it’s gone’.”

Bjergfelt, who has had to balance the rigours of his training schedule alongside his full-time job as an aerospace engineer, says there is more to consider than just riding as hard as possible for an hour. “We did relative tests in May up in Manchester and the one thing that I found there was that after around 40 minutes my hand became quite numb, so that’s going to be interesting, pushing through the different barriers that you get.

“With the Hour Record you have to be really, really conservative in the first 40-45 minutes: you still want to be on pace to beat the record, but you have to be really within yourself, because it’s an effort that comes back to bite you. In that last 10-15 minutes, that’s where hopefully I’ll be on pace, and at the same time I should have enough left in the tank to get the maximum out of myself.”

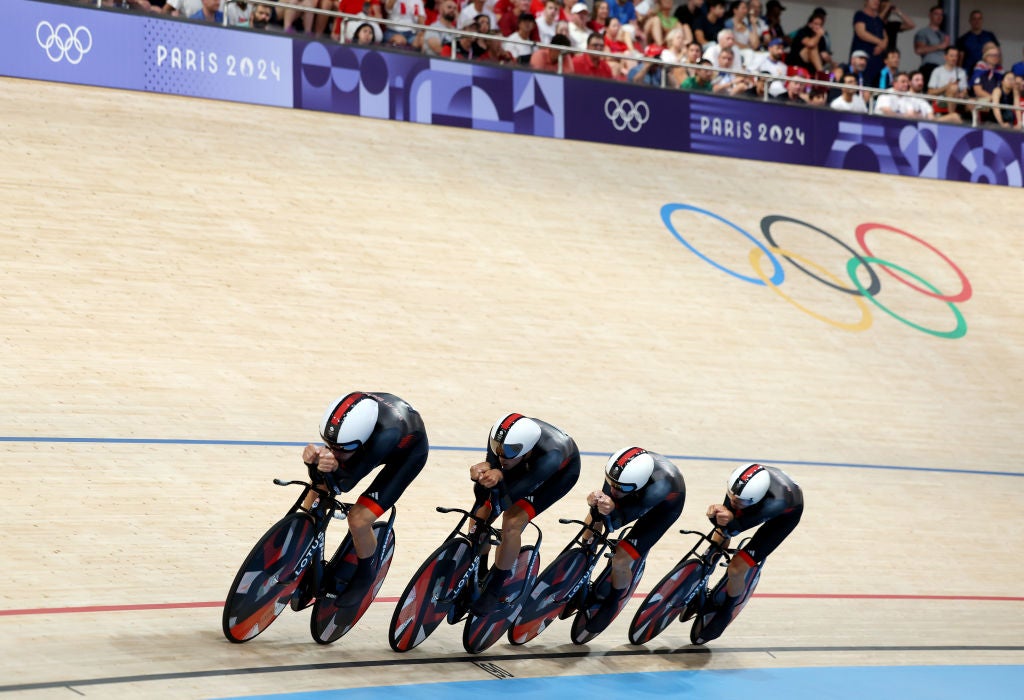

All three riders will be on equipment designed to push them as far and as fast as possible, on the Hope-Lotus Olympic bikes from Paris last year, as well as wearing customised skinsuits. “It’s the fastest bike I’ve ever ridden on the track,” says Bjergfelt. “Technology has moved on so far since the Hour Record was set in 2014. It’d be wrong if I didn’t really smash the record to bits.”

Richardson is similarly confident that history will be made next week. “Nothing’s ever a done deal, ever, but I’m pretty confident that I’m in a really good place to get the job done.”